After his arrival to power in 1933, Adolf Hitler, who pretended to « save the German culture » from falling in decadence because of the new artistic movements such as Dadaism, Cubism or Expressionism, ordered the withdrawal of more than 16.000 works of art from national German museums.

From July 1937, considered as « degenerate », in opposition of the « ideal art » represented by the aryan’s artists, 650 of those works were displayed throughout Germany and Austria. Inaugurated in Munich, Entartete Kunst (« Degenerate Art ») would welcome more than 3 million visitors, from Vienna to Berlin, Weimar, Leipzig or Dusseldorf.

After the invasion of Austria, Sudetenland and Czechoslovakia in 1938, and Poland the next year, nazi Germany entered the war. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring began for the 3rd Reich the largest artistic looting ever known before, which reached its peak in 1940 with the invasion of France, where the « status of Jews » was proclaimed.

Accused of « stealing the wealth of the French people », French administrations banned Jews from access to many professions, confiscated their properties, their businesses, their bank accounts, and especially their works of art. Deprived of any resource, Jews were trapped in arrest, internment, and ultimately deportation.

For the auctionners and auction houses, these thousands of works of art were a real bargain, making of Paris the international hub of the art market. Between 1941 and 1942, more than 2 million works, stolen from national museums and private collections, were sold in the auction houses of the capital, such as Drouot, but also in « free zone », where the collection of Armand Isaac Dorville for example, in exile in Dordogne, was displayed and sold between June 24 and 27, 1942 at the lobby of the Savoy Hotel, in Nice.

« Under the Occupation, it is shortage everywhere! Now at Drouot, everything is sold, and the clatter of the ivory mallets is incessant. »

Emmanuelle Polack, scientific curator of the exhibition.

In the French capital, many art dealers were be contraigned to react quickly to save their works and their businesses.

Pierre Loeb, whose gallery rue des Beaux Arts hosted paintings of Raoul Dufy, Marc Chagall or Joan Miro since 1924, was forced to flee Paris to Cuba, and to hand over the management of his gallery to a friend, Georges Aubry, to save it from an « Aryan administration ». After Loeb’s return from exile, Aubry was very reluctant to return him the gallery. The dispute was solved after the intervention of Pablo Picasso, who was displeased with the whole situation.

One of the most famous galleries in Paris, the Rosenberg Gallery, located at 21 rue la Boétie, was one of the main addresses for avant-garde in France. Like many other merchants, Paul Rosenberg would flee France for the United States, after sheltering 162 works in a safe in Libourne, safe that was finally found and forced by the German authorities on April 1941. Most of these works were storage at the Jeu de Paume, awaiting to disappear. Rose Valland, a conservation assistant at the museum, secretly made an inventory of more than 100.000 works of art transiting in the Jeu de Paume. At the end of the war, more than 60% of those works were found and returned to France, and around 45.000 were restituted to their rightful owners in the next 5 years.

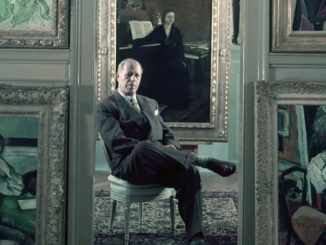

René Gimpel, the « merchant of the impressionists », was another important figure at this time. He was the husband of Adèle Vuitton, niece of the founder of the famous Maison that later would create the trunks and crates to store and ship the paintings of his friends Renoir, Soutine, Matisse or Laurencin. Gimpel also fled Paris in July, 1940. Such as Paul Rosenberg, René Gimpel would hide in his premises at rue Garibaldi, 81 crates containing tens of works, awaiting to be transferred to Monte Carlo. Unfortunately, he never had the opportunity to leave. René Gimpel was arrested and deported in July 1944 to the Neuengamme concentration camp, where he died in January, 1945.

Finally, Berthe Weill’s Gallery, « amie des peintres » (« friend of the artists »), was the first woman merchant of art in Paris. She exhibited and sold paintings of Matisse or Picasso, and will organized in 1920 the very first monographic exhibition of Amedeo Modigliani. During this exhibition, 32 paintings and drawings were presented, including four nudes that would create a huge scandal because of their… hairs. Opened in 1901, the Berthe Weill’s Gallery went bankrupt in 1939 due to significant financial troubles. At the end of the war, to help the woman who had discovered them, six painters organized the sale of 80 of their paintings to her benefit, allowing Berthe Weill to live with dignity until her death, in April 1951.

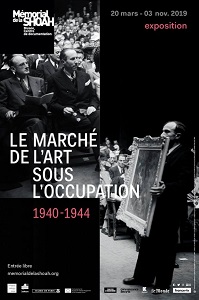

After a meticulous investigation in France, Germany and United States, the exhibition The art market under Occupation. 1940-1944 questions the hidden part of the art market during World War II, and highlights its dark side. With more than 300 documents, photographs, posters, objects and concrete examples, the exhibition tells the story of four prestigious art merchants and the course of the works they showcased, from their spoliation in Paris to their final restitution, like the paintings of John Constable or Thomas Couture, presented in the galleries.

The art market during Occupation, until November 3, 2019 at the Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris.

Around the exhibition:

– Le marché de l’art sous l’Occupation (French version), by Emmanuelle Polack, Tallandier Editions. 336 pages. 21,50€.

More about:

– The museum of lost art, by Noah Charney. Phaidon Press. 296 pages. 19,22$.

– Lost lives, lost art: Jewish collectors, nazi art theft, and the quest for justice, by Melissa Müller and Monika Tatzkow. Vendome Press. 256 pages. 33,54$.

– Museum of the missing: a history of art theft, by Simon Houpt. Sterling Editions. 192 pages. 38,61$.

– Hitler’s art thief: Hildebrand Gurlitt, the nazis, and the looting of Europe’s treasures, by Susan Ronald. St Martin’s Press. 400 pages. 16,99$.

– The lost museum: the nazi conspiracy to steal the world’s greatest works of art, by Hector Feliciano. Basic Books Editions. 340 pages. 19,99$.

– Hermann Goring and the Nazi art collection: the looting of Europe’s art treasures and their dispersal after World War II, by Kenneth D. Alford. McFarland Editions. 269 pages. 39,95$.

Cet article vous intéresse ? Laissez un commentaire.